by Lauren Meier

This article is a shortened and edited version of the research paper I completed for the Certificate in Botanical Art and Illustration Program, now based at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. I earned my certificate in 2025.

Plant taxonomy—the science of naming, describing, and classifying plants—provides the structure scientists use to understand and communicate about plant diversity. For botanical artists, it’s more than a set of scientific labels: classification shapes which plants are studied, illustrated, and preserved in art. For botanical artists, knowing the history of plant taxonomy deepens the connection between art and science and reminds us that every plant portrait is part of a centuries-long dialogue between observation, classification, and beauty.

Ancient Beginnings

Humans began naming plants thousands of years ago, often for their uses in food, medicine, or materials. Ancient cultures in China, India, Egypt, Greece, and Rome documented plants in written texts. In China, as early as 700 B.C.E., scholars recognized categories similar to genus and species. Indian texts like the Atharva Veda described medicinal plants and their morphology.

The Greeks advanced the idea that plants could be grouped by shared traits, not just uses. Theophrastus, often called the “first botanist,” described about 500 species, noting differences in form (trees, shrubs, herbs), flowering patterns, and habitat. Romans such as Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides compiled encyclopedias of useful plants. These early works, often richly illustrated, were primarily herbals—guides for identifying medicinal plants.

Renaissance and the Age of Discovery

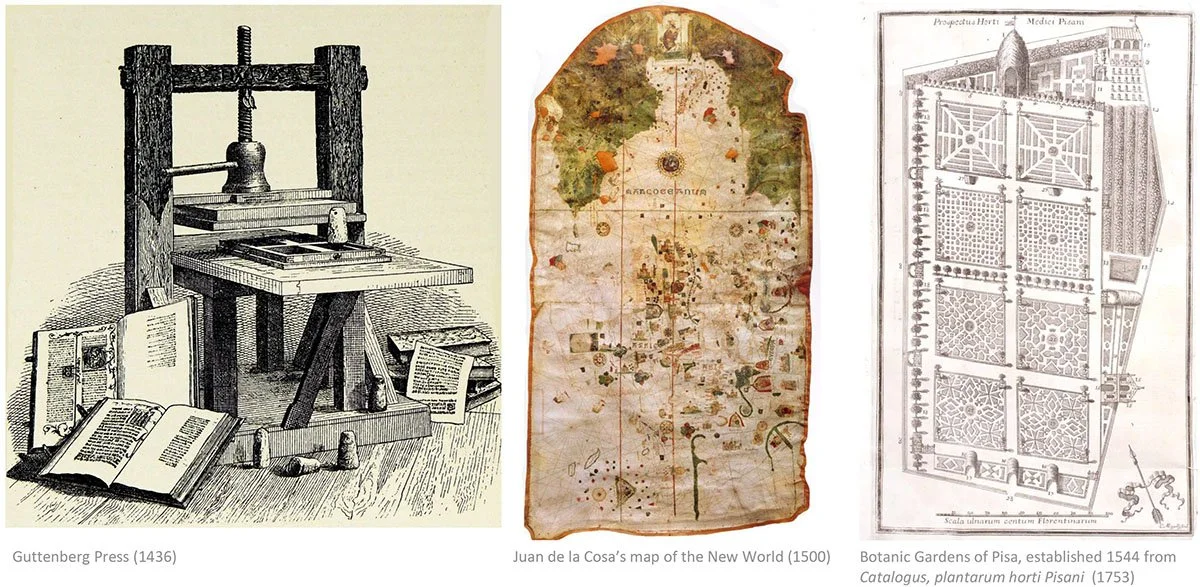

The 14th–17th centuries brought a surge in plant knowledge through exploration, the invention of the printing press, and the creation of botanic gardens. Rediscovered Greek and Roman texts were translated and widely printed, allowing ideas to spread quickly. Voyages by Columbus, da Gama, and Magellan returned plant specimens to Europe, fueling curiosity.

Botanic gardens evolved from medicinal plots to living laboratories. New preservation techniques, like dried plant “herbaria,” allowed year-round study and comparison. Early European botanists such as Otto Brunfels and Hieronymus Bock began illustrating plants from direct observation rather than copying ancient drawings, greatly improving accuracy.

Toward Scientific Systems

By the 16th and 17th centuries, botanists were attempting to classify plants systematically. Andrea Caesalpino grouped plants by reproductive structures (ovaries, fruits, seeds)—a major advance. John Ray in England introduced the concepts of monocots and dicots and defined “species” biologically.

Not all systems were equally sound. Joseph Pitton de Tournefort’s classification based mainly on flower corolla shape was easy to use but oversimplified—still, it influenced later work.

Linnaeus and the Binomial System

Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) revolutionized naming by introducing the binomial system—two names (genus + species) for each plant. This simplified long, unwieldy descriptive names. He organized plants into classes and orders based largely on the number of stamens and pistils, creating what’s called an artificial system because it relied on a single trait.

His Species Plantarum (1753) is considered the start of modern botanical nomenclature. While his focus on flower sex organs was limiting, the binomial format became universal and is still the basis for naming today.

Natural Classification

Late 18th-century botanists began grouping plants by overall similarities (natural systems) rather than one characteristic. The de Jussieu family emphasized fruit, seeds, and embryos, leading to the separation of seed plants from spore plants. Augustin de Candolle expanded on this, describing many plant families still recognized today.

Darwin’s Evolutionary Influence

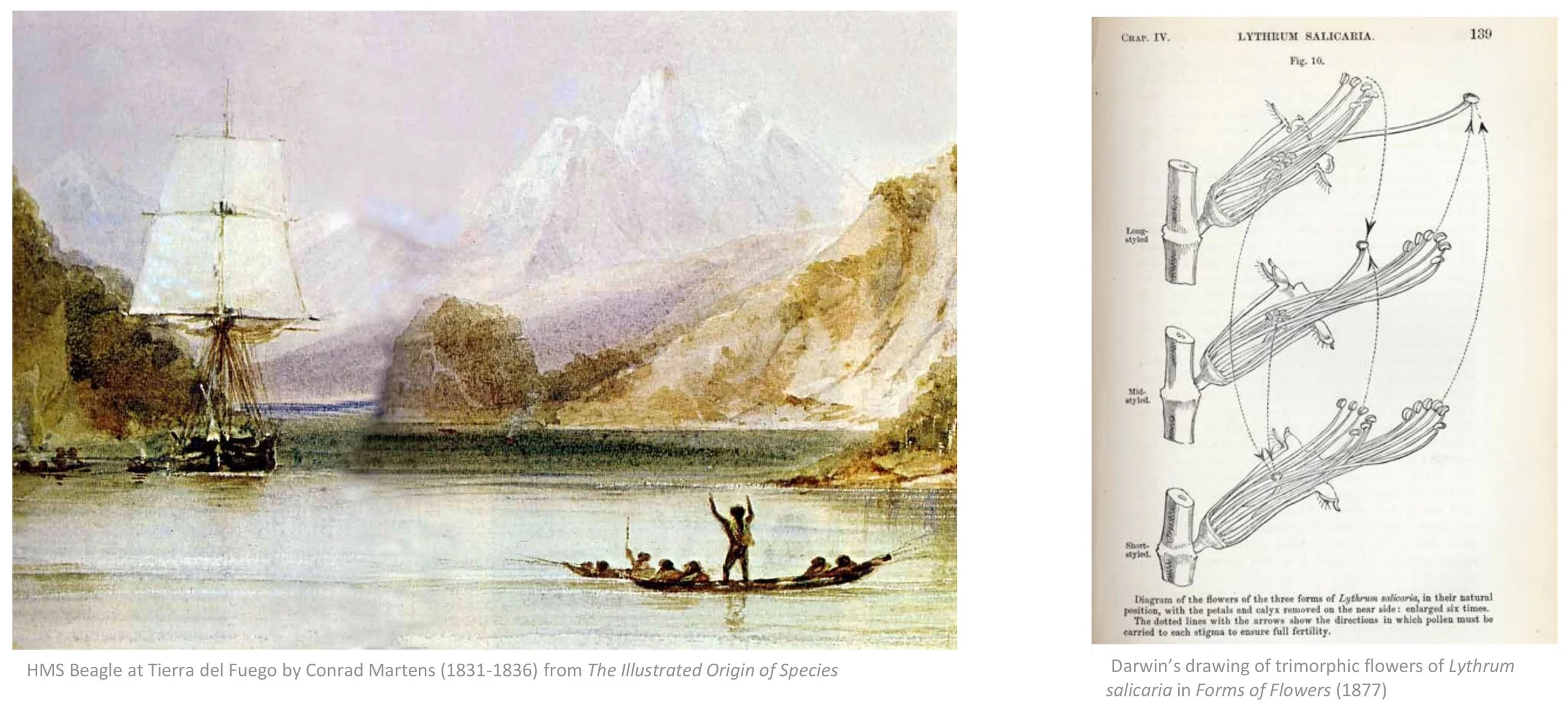

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) introduced evolution and natural selection, shifting taxonomy toward understanding relationships over time. Darwin’s collaborations with Joseph Hooker helped inspire the Bentham & Hooker system, which organized plants into families and orders based on shared traits and geographic distribution. This became the standard into the early 20th century.

Phylogenetic Classification

In the late 19th century, taxonomists began arranging plants according to evolutionary lineage (phylogenetic systems). Adolf Engler and Karl Prantl’s Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien organized plants from “primitive” to “advanced,” incorporating anatomy, morphology, and geography. Their system replaced Bentham & Hooker’s in many institutions.

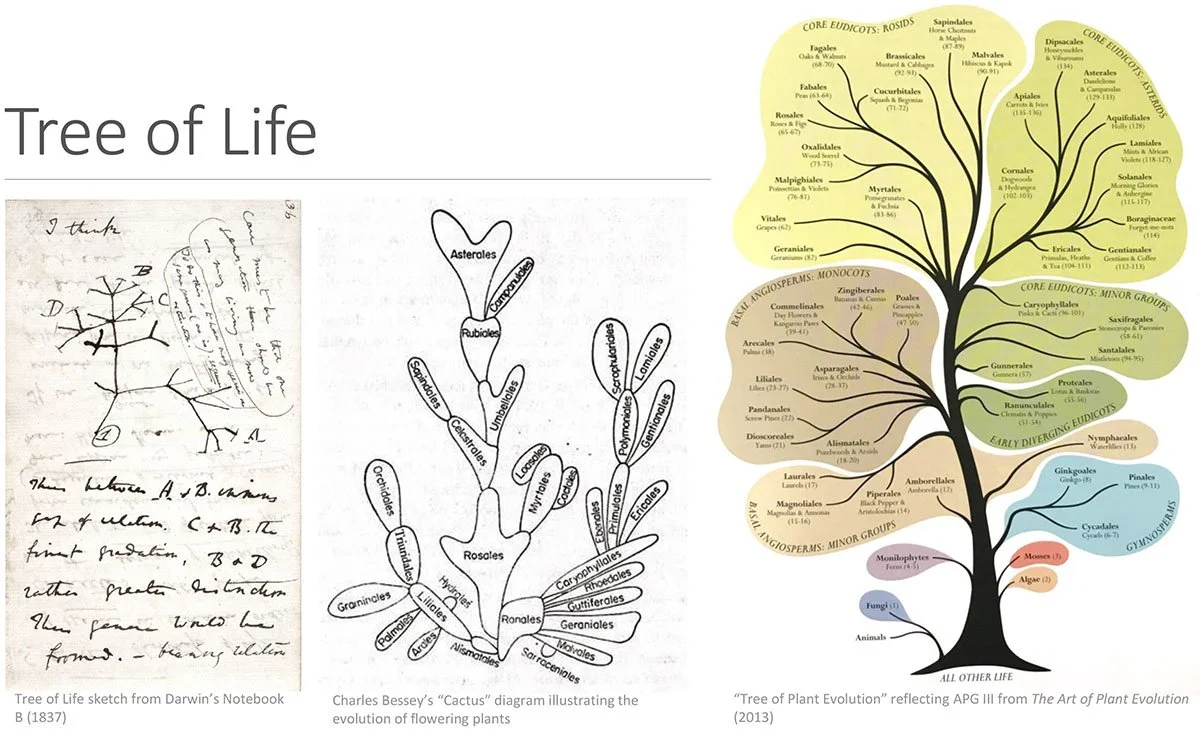

In the U.S., Charles Bessey proposed “dicta” for judging evolutionary advancement (e.g., woody plants are primitive, herbs derived). His diagrams, like the “cactus” tree of life, visually mapped plant evolution—a concept important for artists interpreting plant relationships.20th-Century Advances

Numerous botanists refined classification in the early 1900s, including John Hutchinson, Lyman Benson, Armen Takhtajan, and Arthur Cronquist. Takhtajan and Cronquist both produced influential systems that separated flowering plants into monocots and dicots with further subdivisions, anticipating adjustments once genetic data became available.

DNA Revolution and the APG System

By the late 20th century, DNA sequencing allowed scientists to study plants’ genetic relationships directly. This transformed classification, resolving debates that morphology alone couldn’t settle.

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG), formed in 1998, brought together botanists worldwide to create a consensus classification for flowering plants. APG uses genetic data to define monophyletic groups (those with a single common ancestor). Notably, it redefined “true” dicots as eudicots, reorganized monocots, and reshuffled families like the lilies and irises. APG’s fourth version (2016) is the current global standard.

The Tree of Life in Visual Form

Darwin’s first “tree of life” sketch illustrated the branching of species from common ancestors. Later diagrams by Bessey, Takhtajan, and modern APG visualizations turn evolutionary relationships into accessible charts. For botanical artists, these diagrams parallel the way botanical illustration can tell the story of a plant’s place in the natural order.

Lauren Meier holds a BA in Botany from Pomona College and a Masters of Landscape Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. For four decades, she focused on the documentation and preservation of cultural landscapes nationwide, including contributing to several books related to the work of the Olmsted firm. Meier began studying botanical art in 2018, completing the certificate in 2025. Her botanical art emphasizes the relationship between the science of plant morphology and art. She currently teaches Intro to Botany through Drawing and New England Flora at Mass Hort.